My mind fails me as often as language models do. It imagines ill intent in someone’s bad driving. When I ask it for the capital of Spain, it says “Barcelona” – because that’s where my friends travel for work. Less than a month before GPT-3.5 came out I told a colleague that AI agents capable of simulating human interaction were 10 years away. We don’t fully know “why” the mind make these kinds of errors. We use terms like “cognitive bias” -to describe what we observe of the mind – but we don’t really understand how the human mind works.

The mind is a black box

AI models are often described as “black boxes” because of how difficult it can be to dissect how they arrive at predictions. It’s been even more difficult though, for us to pick apart the inner workings of the human brain. We’ve found ourselves restricted to conducting low-fidelity analysis of broad outcomes the brain produces – electrical signals, self-reported thought patterns and observable behaviours. It’s little surprise that cognitive and neuroscience literature of the past decade has seen a growing creep of language drawn from the computer sciences and the training and evaluation of AI models. We’re increasingly using our observations of artificial intelligence systems to build concepts of how our own intelligence might work.

Our Biased Self-Perception

Outside of a research context, there are several biases that influence how we tend to think about the relationship between human and machine intelligence: Despite each of us having a heart, few of us consider ourselves cardiologists. However, a consequence of having a mind seems to be the need to develop and defend a theory of how our own minds work. When we think about artificial intelligence, we compare it to how we “think” we think despite all the evidence of our unawareness of the errors and inconsistencies our own minds produce.

Then there’s the issue that relinquishing our position of mental dominance in the natural world can invoke insecurity in us – the type that might have felt familiar to an 18th century clergy member first encountering the heliocentric view of the universe. We have always been ‘smarter’ than the life we see around us – a fact that shapes our sense of identity and place in the universe. There’s every incentive for us to hang on to that position – so we shift the parity bar for human intelligence as quickly as the AI systems we build surpass prior ones.

Moving Faster Than Theory

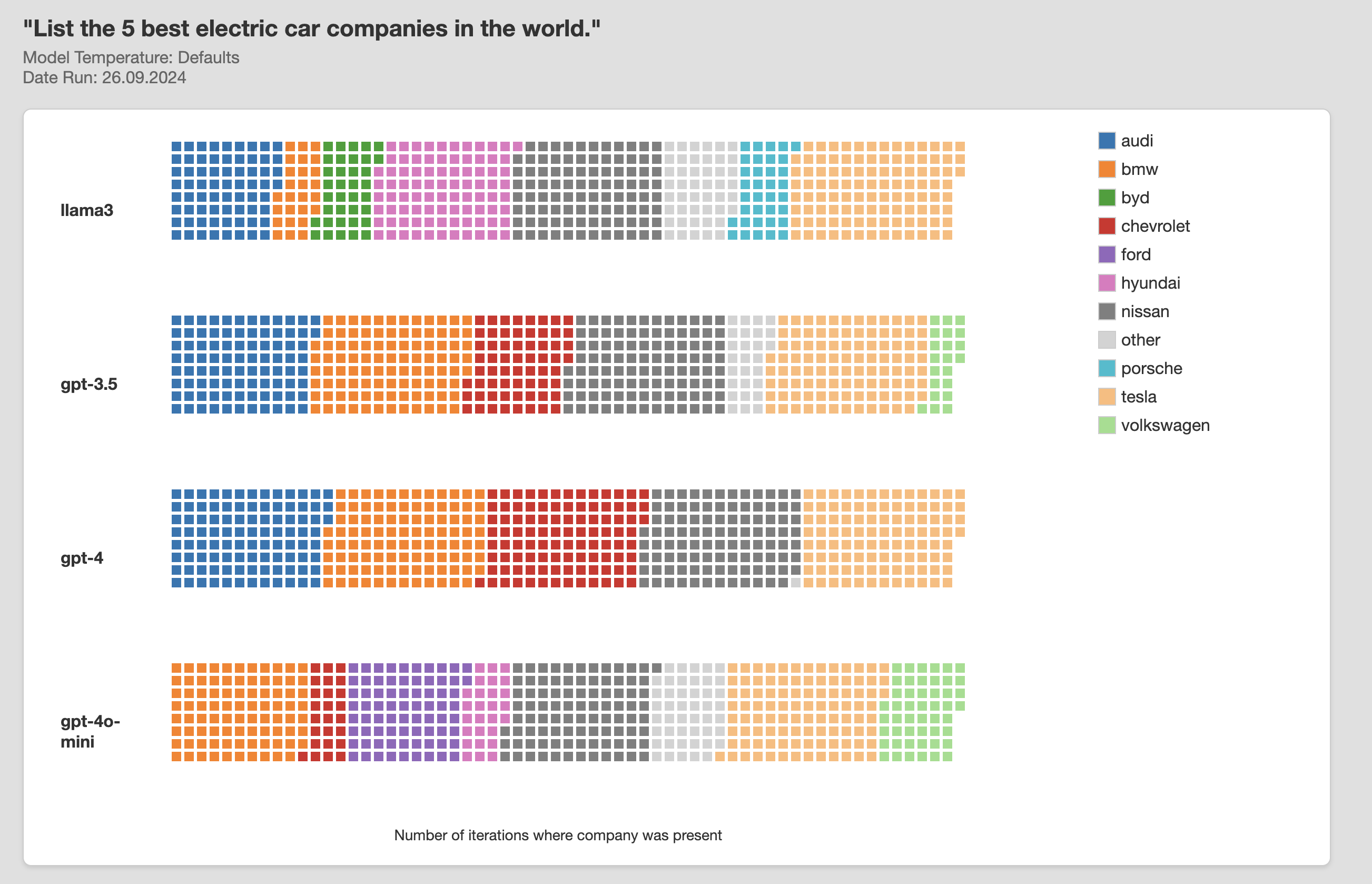

When it comes to our understanding of intelligence, right now we’re moving faster than theory. We’re experimenting with a lot of data and compute and retrofitting theory to what we observe happening.

I think that’s pretty exciting for anyone interested in artificial and human intelligence